This is a repost of my 2013 article for Thunderbolt.

Dishonored’s city of Dunwall is one of the most memorable and immersive cities in this generation – once experienced it lingers in the imagination, imploring you to revisit its murky streets and secure its future. Although it exists in an undetermined time and another reality, Dunwall feels real and engaging from the game’s beginning. Moribund due to the corruption of its keepers, Dunwall is still a living, breathing and believable city.

This is due to the experience and talent present within Dishonored’s developers, Arkane Studios, and a process that allows for more creative input. As noted by Gamefront, usually conceptual artists and architects are rarely involved in game design past the pre-production stages, but level designers worked alongside architects throughout Dishonored’s design.

As noted in this interview with The Creators Project, visual design director Viktor Antonov reveals the game was originally going to be set in medieval Japan. This was avoided due to the, largely European, development team’s lack of knowledge of the era, and the setting was instead changed. Art director Sebastien Mitton and Antonov shifted their focus to Victorian London, specifically the 1660s, the time of the Great Fire of London and the Great Plague epidemic. The two artists conducted detailed research by travelling to both London and Edinburgh, surveying and recording each city’s architecture. Besides this, the pair were influenced by a wealth of artistic sources; paintings and architecture, including the beginnings of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Renaissance.

Like many of the settings in the works of H.P Lovecraft, Dunwall has a strong dependence on the surrounding ocean – its economy is based around whale oil and – much like the River Thames in London, the Wrenhaven River bisects the city. It’s a shame there’s no olfactory videogame technology at present, as Dunwall’s coastal breezes would surely bring in the oceanic scent of salt and seaweed. Besides evoking the murky and supernatural atmosphere of Lovecraft’s coastal fishing towns, Dunwall has also genuinely captured the feel of London’s streets – something Antonov intended, as revealed to The Creators Project:

“We wanted to study the rhythms existing on London streets, its architecture, as well as the general mood which is specific and interesting, something we wanted to preserve.” For overt comparisons, look at the similarities between Dunwall Tower and the Tower of London, or Kaldwin’s Bridge and London Bridge. Besides this, Dunwall’s architectural features are often lifted directly from London’s , such as its “specific rooftops […] smokestacks and façade ornaments…”, as Antonov stated in an interview with Press2Reset.

Much like London, Dunwall has been built upon the remnants and vestiges of what has come before it. London is known to date back at least as far as The Bronze Age, whilst the Outsider-worshipping ancient civilisation that once existed on the site of Dunwall is said to date back 1,000 years before the events of Dishonored. This helps lend Dunwall its archaic atmosphere, a feature that’s expertly contrasted by the prevalence of Sokolov’s advanced industrial technologies such as the arc pylon, Walls of Light, Tallboys and rail cars in the city (interestingly, Mitton rejects the ‘Steampunk’ label often associated with the game).

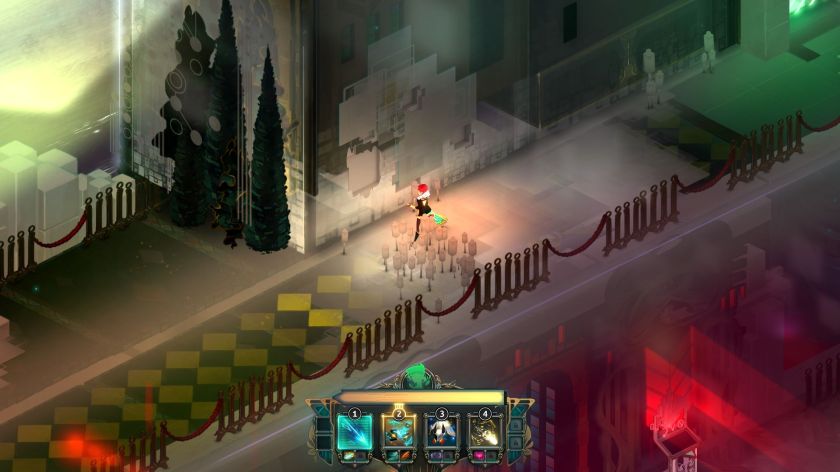

Contrasts are perpetuated throughout Dunwall’s locations, with the architecture often informing the narrative. The divide between Dunwall’s upper and lower classes is blatantly established by its buildings. The wealthy denizens live in the heavily guarded mansions of the Estate District and Dunwall Tower, often in elevated, well-lit positions on the city’s topography – serving to physically place them higher than their oppressed and suffering subjects. The Estate District’s Boyle Mansion, which features elements of the Queen Anne style of architecture such as sash windows in painted boxes, stone quoins emphasising its external corners and steps leading to a carved stone door case, is a prime example of this elevated affluence.

The lower class are forced to live in run-down and darkened Victorian-esque masonry-constructed homes, cramped into undesirable areas such as the crime-ridden slums of the Distillery District. It’s these cramped and unclean living conditions which undoubtedly helped the terrible rat plague to spread with such crippling efficiency, before the City Watch’s curfews and quarantines further afflicted the unwealthy and unhealthy populous.

Looking through the eyes of the supernaturally agile Corvo Attano, players are able to traverse Dunwall’s many areas in a variety of ways. Either skulking through its sewers, shifting at speed over ground level or darting across its rooftops – you experience the city from a number of varying perspectives and, by using Possession, can even experience the city from the point of view of its vermin. This gives you a comprehensive overview of the city not offered in many other videogames, and this allows you to forge a strong link with Dunwall’s layout. Further to this, you must use the city’s many structures and spaces to your advantage in order to progress through the game; hiding in its shadows, using its brick and stone as makeshift cover and dropping from its heights to incapacitate your foes.

The Flooded District serves as a dark jewel in Dunwall’s environmental crown – a broken-down area made up of dilapidated factories and other failing buildings. Given its name due to a collapsed water barrier, the area is a haven for criminals and cultists; a cesspool of hostility. The local fauna, the horribly mutated river krust molluscs, irksome hagfish and streamlined but feral wolfhounds, all serve to further increase the overbearing disarray and violence in the area by attacking Corvo at every opportunity. Dumped by the ruthless City Watch, the bandage-wrapped carcasses of plague victims litter the district like an awful garnish on a last meal prepared for the dark god of pestilence. Like The Glow in Fallout or the Hollows of Gears of War 2, The Flooded District is not a place you wish to linger unless you’re suitably equipped.

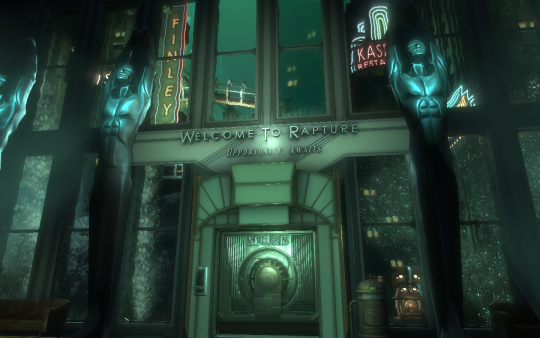

Dunwall is a triumph of design, one that surpasses both its creators’ previous works (Antonov helped design Half-Life 2’s City 17) as well as becoming something more than the sum of its parts. If games such as BioShock, Portal and Shadow of The Colossus are to be put forth as videogame examples of art, then on the basis of Dunwall and its overall design quality, so should Dishonored, as Antonov’s intentions are purely artistic and have been purely realised:

“Subjectively, I would like the players to end the game with memories of Dunwall as if they had visited a real city that they found very exciting and intense. I want it to leave them with memories of lights, noises, fear, and beauty they could never have in real life, anywhere in the world.”

Source: Dishonored: Dunwall, a fully-realised artistic vision